Should your AI solution rely on a single reasoning entity, or on a coordinated team of specialized agents? The answer depends on your system’s complexity, your cost constraints, and how far you expect it to scale.

Recent benchmarks show multi-agent systems achieve 23% higher accuracy on reasoning tasks compared to single-agent counterparts[5]. At the same time, single-agent solutions handle roughly 80% of common use cases well, and they cost a fraction of what multi-agent deployments require[5][6]. The tradeoff is real: multi-agent systems consume approximately 15× more tokens than single-agent interactions[6], and coordination overhead can degrade sequential reasoning performance by 39–70%[10].

What follows covers both architectures in detail: the design decisions that matter in production, and the failure modes that most comparison articles skip.

Understanding Single-Agent and Multi-Agent Architectures

The choice between centralizing intelligence in one agent or distributing it across many shapes the entire development trajectory of an AI system. It determines complexity, cost structure, failure behavior, and ceiling for capability.

What is a single-agent system?

A single-agent system combines all reasoning, memory, and tool execution into one AI entity. It operates autonomously within a defined environment to achieve specific goals[1], adapting its approach as conditions change without relying on coordination with other agents[2]. These systems go well beyond basic chatbots. Where chatbots depend on human input at every step, single-agent systems maintain their own decision loops and require minimal human oversight[2].

Single agents perform well on focused tasks: analyzing large datasets, running software test suites, or resolving customer service tickets with contextual understanding[2].

A functional single-agent system requires four components working together: an LLM reasoning engine that processes inputs and generates decisions, a memory system that maintains context across sessions, a tool integration layer for connecting to external services and APIs, and a planning module that decomposes complex goals into executable steps[1]. The interdependence of these components is what separates a capable agent from a glorified prompt chain.

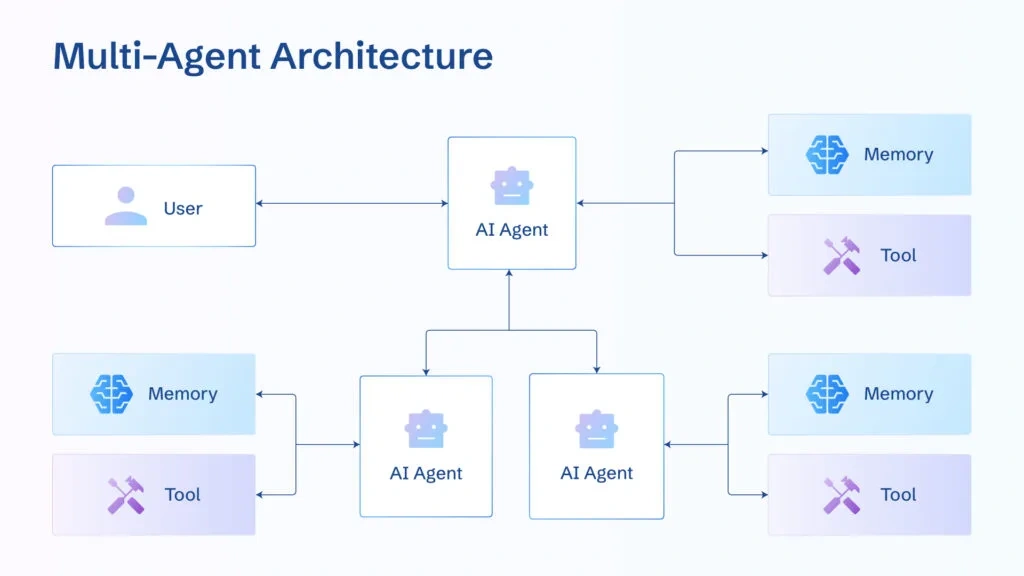

What is a multi-agent system?

Multi-agent systems (MAS) coordinate multiple AI agents, each with its own reasoning loop, memory, and tool access, to complete tasks collaboratively[3][4]. The agents communicate with each other directly or through changes to a shared environment, dividing complex problems into sub-tasks that would overwhelm any single agent[3].

The performance gains can be substantial. Anthropic’s internal testing found that a lead-agent/helper-agent architecture outperformed single agents by 90.2%[5]. That improvement stems from the system’s ability to distribute work across agents with separate context windows. Parallel reasoning across those windows is something a monolithic agent cannot replicate[5].

Key differences in structure and behavior

The structural gap between these architectures shows up in several dimensions:

- Control structure: Single-agent systems centralize all decisions in one entity. Multi-agent systems distribute control across semi-independent agents, each responsible for its own domain[5][1].

- Computational cost: Single-agent systems require fewer resources, which makes them accessible to teams with limited infrastructure budgets[5][4].

- Complexity ceiling: Multi-agent systems handle larger, more complex problems by distributing workload across specialists. They often outperform single agents on tasks that benefit from shared resources and parallel optimization[3][5].

- Communication overhead: Every handoff between agents introduces latency and requires explicit state management. Coordination difficulty scales with the number of agents[5][1].

- Token consumption: Multi-agent systems use roughly 15× more tokens than chat-based interactions, while individual agents consume about 4× more than standard calls[6]. The task must justify that cost through measurable performance gains.

- Failure behavior: A single-agent system either works or fails entirely. Multi-agent systems distribute risk; if one agent fails, others continue operating[4].

For most organizations, single-agent systems remain the correct starting point for predictable, well-scoped tasks[5]. Multi-agent architectures become necessary when solutions require more than three to five distinct functions or cross security boundaries[5].

The Case for Multi-Agent AI Systems

As organizations push AI systems toward more complex workflows, the constraints of single-agent design become apparent. Monolithic systems have hard limits on what they can do at scale, and those limits are driving the shift toward multi-agent architectures.

Why single-agent systems hit scalability limits

Even the most capable single-agent systems run into fundamental constraints when tasks require expertise across multiple domains: market research, competitive analysis, legal compliance, and creative strategy simultaneously[5]. Monolithic architectures become bottlenecks on time-sensitive parallel workloads, such as analyzing hundreds of contracts concurrently[5].

The problem compounds when different components require specialized tooling with distinct security requirements and operational cadences[5]. A rigid, single-agent framework cannot easily adapt to new task types or environments[7], and complex workloads create a performance ceiling that the architecture cannot overcome[3].

Google’s research introduces a significant counterpoint, though. Tasks requiring strict sequential reasoning (planning, in particular) see multi-agent performance degrade by 39–70% compared to a single agent[3]. Communication overhead fragments the reasoning chain, and each agent ends up with an insufficient share of the total cognitive budget. Above 45% single-agent accuracy on a given task, adding more agents frequently produces negative returns because coordination costs outweigh the marginal improvement[3].

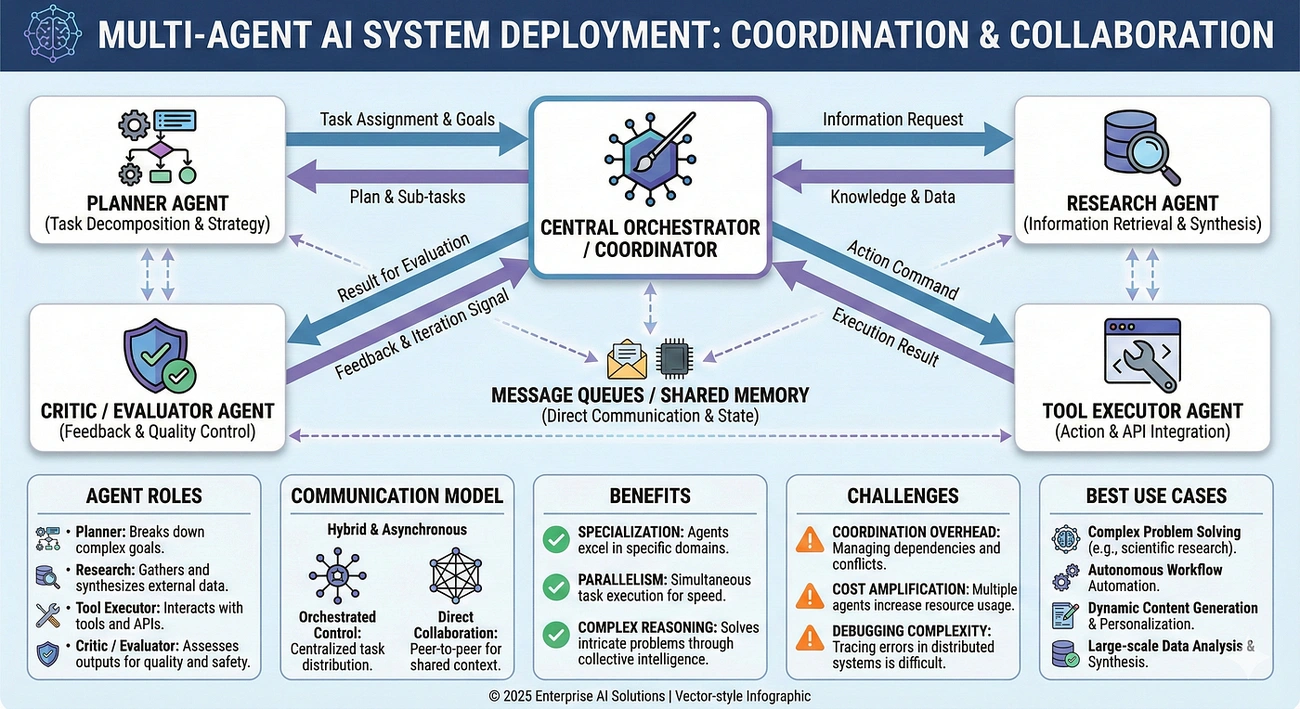

How multi-agent systems mirror human teams

Multi-agent systems distribute cognitive load across specialized agents in much the same way human organizations divide labor. Multiple agents work on different facets of a problem simultaneously, which reduces total processing time. Each agent optimizes for a specific task domain with tailored training and knowledge bases. And when one agent encounters an error, the rest of the system continues to function[5].

Coordination can follow hierarchical or flat models[5]. In hierarchical setups, an orchestrator delegates to specialists. In flat configurations, agents negotiate directly with peers. The AgentVerse framework demonstrates the latter approach: architect, designer, and engineer agents engage in structured discussion to reach consensus, producing better outcomes on diverse problem-solving tasks than any individual agent achieves alone[6].

Multi-agent systems in production

Several industries have moved multi-agent systems past the proof-of-concept stage.

In healthcare, AI tumor boards coordinate diagnostic, vital-sign monitoring, patient history, and treatment planning agents. Each specialist contributes a recommendation, and the system synthesizes them to support clinical decision-making[5].

Salesforce launched Agentforce, extending their generative AI tooling from conversational assistants to automated agents that handle service cases, coach sales representatives, and allow organizations to build custom agent configurations[8]. Edmunds runs a multi-agent ecosystem where specialized agents manage distinct workflow segments at machine speed[9].

Georgia Tech researchers built multi-agent systems for surgery, search and rescue, and disaster response applications. Their InfoPG architecture supports iterative inter-agent communication, and the resulting collaborative strategies are sophisticated. In one simulation, agents independently formed a triangle formation where the lead agent absorbed damage while two flanking agents eliminated the threat[10]. Financial institutions use similar architectures for algorithmic trading, where specialized agents handle dataset analysis, pattern detection, trade execution, fraud monitoring, and compliance checks in parallel[11].

Building a multi-agent system or evaluating whether your workload justifies the transition? Talk to our team about architecture design and production deployment.

Designing a Multi-Agent Architecture

Most multi-agent failures are architecture failures. Agent specialization, communication patterns, and state management are the three design axes that determine whether a multi-agent system outperforms a single agent or just costs more than one.

Agent roles: researcher, planner, executor, editor

Role assignment coordinates agents by matching tasks to capabilities[12]. Clear role boundaries prevent duplication and ensure each agent contributes to the overall objective without interfering with others. The standard role taxonomy includes researcher agents (information gathering and context assembly), planner agents (problem decomposition and strategy), executor agents (plan execution and tool interaction), and editor agents (output review, refinement, and verification).

Roles can be static or dynamic depending on the use case[12]. In a manufacturing context, for example, separate agents might handle production scheduling, order processing, and shipping logistics. Each agent focuses on its own domain while contributing to shared production goals.

Communication protocols and the orchestration layer

The orchestration layer transforms independent agents into a unified system[2]. Without effective orchestration, even highly capable agents will duplicate effort, contradict each other, or pursue irrelevant sub-goals.

A typical orchestration layer combines three functional units: a planning unit that decomposes high-level goals into agent-level tasks, a policy unit that enforces boundaries and constraints, and an execution unit that dispatches work to agents and manages their outputs[2]. Communication protocols define the standards for information exchange between agents[2].

The most common production pattern is centralized supervision, where a single supervisor agent handles all routing and coordination. Hierarchical delegation adds layers to that model: supervisors delegate to sub-supervisors, who in turn manage progressively more specialized agents. Peer-to-peer networks abandon central coordination entirely and let agents communicate directly, which works well when agents have roughly equal authority and complementary capabilities.

Memory and state management in distributed agents

Memory is what separates a stateful agent from a stateless language model[13]. Without persistent memory, an agent forgets what happened moments ago, which makes multi-step workflows impossible. Production memory architectures typically implement three layers: short-term memory for the current conversation or task context, long-term memory for information that persists across sessions, and episodic memory that records and retrieves sequences of past events. Implementation requires tools like Redis for real-time state management and vector databases for efficient semantic retrieval[13]. For voice applications, the entire memory retrieval pipeline must complete in under one second[13].

Frameworks and SDKs for multi-agent development

Several frameworks reduce the engineering effort required to build multi-agent systems, each with a different design philosophy.

OpenAI’s Agents SDK provides fundamental building blocks: agent definitions, task handoff mechanisms, and validation guardrails[14]. It prioritizes a low learning curve while covering the essential feature set. Google’s Agent Development Kit (ADK) supports hierarchical multi-agent structures with automatic routing, where agents delegate to specialists based on capability descriptions[15].

CrewAI takes a role-based approach that treats agents as members of a coordinated crew, while LangGraph models agent behavior as graph nodes connected by state transitions[16]. Framework selection should be driven by your specific requirements for coordination complexity, memory persistence, and production deployment constraints.

Deployment and Tooling: From PoC to Production

This is where most multi-agent projects stall. The decisions below, covering orchestration frameworks, integration architecture, security, and cost controls, need to be resolved before anything goes live.

Choosing the right orchestration framework

CrewAI works well for role-based collaboration, particularly content creation pipelines and automated research workflows[1]. Its autonomous delegation and flexible task management model suits complex business applications[4]. Microsoft Research’s AutoGen takes a different approach: it models all inter-agent communication as asynchronous conversations between specialists, which reduces bottlenecks during long-running tasks[4] and fits code generation and complex problem-solving scenarios well[1].

LangGraph stands apart from both. Part of the LangChain ecosystem, it provides granular control through a graph-based programming model[4] where workflows are defined as explicit execution paths with precise state transitions. The sophistication comes at a cost in learning curve, but for enterprise applications with complex decision logic, LangGraph’s state management, memory persistence, and human-in-the-loop capabilities are more complete than what the other frameworks offer[17].

Integrating with Azure AI Foundry and OpenAI

Azure AI Foundry Agent Service provides enterprise-grade infrastructure with built-in security and compliance tooling[18]. The service handles thread management, message routing, run execution, tool invocation, safety filtering, and model deployment as native features[19].

For production deployments, hosting multi-agent systems in Azure Container Apps adds private networking, Key Vault integration, and end-to-end monitoring[19]. Azure Foundry’s management interface supports deployment, testing, and parameter adjustment while providing visibility into how configuration changes affect agent reasoning and coordination[20].

OpenAI’s Agents SDK offers a leaner alternative with core primitives for agents, handoffs, and validation guardrails[18]. Teams with less complex requirements can move from concept to working multi-agent system quickly with this approach.

Security, compliance, and governance

Multi-agent systems require zero-trust architecture as a baseline. Every inter-agent communication must be treated as untrusted[3], with authentication at each interaction point, authorization on every message, and continuous verification of agent behavior[7]. Governance frameworks should define roles, permissions, and communication rules before any agent goes live[3], and granular tool access control with centralized policy enforcement is a prerequisite, not a later-stage hardening exercise[7].

Operational visibility matters just as much as access control. Teams need monitoring across tool usage, inter-agent messages, memory access patterns, data flow logs, and agent behavioral indicators[7]. Without it, security incidents go undetected and regulatory compliance becomes unverifiable.

Cost optimization

Token consumption is the primary cost driver in multi-agent systems, and it can escalate quickly without deliberate controls[21].

Designing specific communication protocols that define exact information flows between agents prevents unnecessary token expenditure[21]. Breaking complex workflows into smaller, independent sub-tasks reduces the coordination overhead on each individual operation. Caching external tool call results eliminates duplicate API requests, and per-agent rate limits prevent cost spikes from runaway loops[21].

Memory management has a direct cost impact. Smart compression that stores key insights instead of raw conversation logs keeps memory costs manageable[21]. A sliding window approach that evicts stale context while preserving essential information maintains performance without unbounded memory growth.

Challenges and Tradeoffs of Multi-Agent Systems

Distributed AI architectures bring a class of technical problems that single-agent systems never encounter. The severity of each varies by deployment, but none can be ignored.

Coordination overhead and latency

Inter-agent communication carries significant overhead. Multi-agent systems consume 15× more tokens than standard chat interactions[6], and coordination latency scales non-linearly: a 5-agent system incurs roughly 200ms of coordination time, while a 50-agent system exceeds 2 seconds[5].

Sequential reasoning tasks suffer most. Any multi-agent configuration degrades performance on strict step-by-step reasoning by 39–70% because communication interrupts the chain of thought[10]. Agents lose too much of their available context to coordination overhead, leaving insufficient capacity for the actual reasoning task.

Error propagation presents a related risk. When agents operate independently without communication, errors compound by a factor of 17.2×. Systems with a central orchestrator reduce that multiplier to 4.4×[10], which underscores why orchestration design is a reliability decision as much as a performance one.

Debugging and observability

Failures in multi-agent systems are, as one research team described them, “not only common but incredibly difficult to diagnose”[22]. Each agent maintains its own working memory, which creates information silos that make end-to-end troubleshooting difficult.

Effective debugging requires detailed memory tracking (all reads, writes, and deletes), turn-by-turn state snapshot comparisons, and automated failure mode detection[23]. Standard debugging techniques break down when nearly identical prompts produce different outputs, or when a single error hides among thousands of conversation turns. Teams need observability platforms that provide structured visualization of agent interactions and context flow. Manual log-file archaeology does not scale; navigable diagnostic views do[24].

Emergent behavior and autonomy management

Agent interactions sometimes produce system-level outcomes that no one designed or anticipated[5]. These emergent behaviors arise naturally from the interaction dynamics, and they can be beneficial or destructive. Calibrating the right level of agent autonomy is one of the harder design problems: too much freedom produces unpredictable behavior, too little makes agents rigid[9], and greater autonomy also increases the system’s attack surface[11].

Market-based coordination mechanisms and contract net protocols help manage this tension by giving agents structured ways to negotiate resource allocation and task distribution[9]. Without such guardrails, a localized failure can propagate across multiple components and degrade the entire architecture[23].

Conclusion

Single-agent systems handle the majority of common AI use cases well, and they remain the correct default for teams with focused requirements and constrained budgets. Their simplicity, lower resource consumption, and straightforward implementation make them the practical choice for most initial deployments.

Multi-agent architectures earn their complexity when tasks demand expertise across multiple domains, parallel processing of time-sensitive workloads, or fault tolerance that a monolithic system cannot provide. The cost is real: higher token consumption, more difficult debugging, and coordination overhead that can actively degrade performance on sequential reasoning tasks. These tradeoffs require careful management of agent roles, communication protocols, memory architecture, and security controls before any production deployment.

The trajectory of AI system design follows the same pattern as human organizations: division of labor and structured collaboration, not ever-larger individual entities. Frameworks like CrewAI, AutoGen, and LangGraph now provide production-grade tooling for orchestrating these systems. For most teams, the practical question is no longer whether to adopt multi-agent architectures but when workload complexity justifies the transition. Those who plan that progression deliberately will be best positioned to extract value from both approaches as their requirements evolve: start with focused single-agent deployments, then scale into coordinated specialist teams when the work demands it.

Whether you are starting with a single-agent deployment or scaling into multi-agent orchestration, Innervation’s platform handles the infrastructure so your team can focus on the problem.

Key Takeaways

- Default to single-agent systems – They cover roughly 80% of standard use cases at lower cost and with simpler implementation. Start here unless you have a specific reason not to.

- Multi-agent architectures outperform on complex, multi-domain tasks – Up to 23% higher accuracy on reasoning benchmarks through specialization and parallel execution. The gains disappear on strict sequential reasoning tasks, where performance degrades by 39–70%.

- Budget for 15× token consumption – Targeted communication protocols, caching, and memory compression are essential cost controls.

- Define agent roles and communication protocols before building – Researcher, planner, executor, and editor agents with clear boundaries prevent the coordination bottlenecks that degrade multi-agent performance.

- Invest in observability early – Multi-agent failures are difficult to diagnose due to context fragmentation across agents. State tracking, memory auditing, and structured visualization are prerequisites.

Frequently Asked Questions

Single-agent systems consolidate all reasoning, memory, and tool use in one entity. Multi-agent systems distribute those capabilities across specialized agents that coordinate to complete tasks. The tradeoff: multi-agent systems offer superior scalability and parallel processing at the cost of higher coordination overhead and token consumption.

When your tasks require diverse expertise across multiple domains, or when you need to process time-sensitive workloads in parallel. If a single agent can handle the job with acceptable performance, it should. Multi-agent complexity is only justified when single-agent systems demonstrably hit a ceiling, typically beyond three to five distinct functions or across security boundaries.

Coordination overhead and latency top the list. A 5-agent system incurs roughly 200ms of coordination time; at 50 agents, that exceeds 2 seconds. Debugging distributed systems is the second major challenge, because each agent maintains its own state and working memory, which fragments the diagnostic picture. Emergent behavior is a third category: agents sometimes interact in ways nobody designed, and those interactions can be beneficial or destructive. All of these compound with the significantly higher computational resource and token requirements that multi-agent systems carry.

Token consumption increases by approximately 15× compared to single-agent interactions, which is the primary cost driver. Performance gains depend on the task: complex reasoning tasks see up to 23% accuracy improvement through specialization and parallelism, but strict sequential reasoning tasks can degrade by 39–70% due to communication overhead fragmenting the reasoning chain.

AutoGen (asynchronous conversations, from Microsoft Research), CrewAI (role-based collaboration), and LangGraph (graph-based workflow orchestration, LangChain ecosystem). They differ substantially in coordination model, memory handling, and production-readiness, so framework choice depends on your specific deployment requirements.

References

- Best AI Agent Frameworks in 2026: CrewAI vs AutoGen vs LangGraph (Medium)

- Multi-Agent Systems Architecture (ArXiv)

- Multi-Agent Security (Knostic)

- AI Agent Comparison (Langfuse)

- Stability Strategies for Dynamic Multi-Agents (Galileo AI)

- Why Your Multi-Agent AI System Is Probably Making Things Worse (ImaginEx Digital)

- Multi-Agent System Security (MintMCP)

- 10 Reasons Why Multi-Agent Architectures Will Supercharge AI (InformationWeek)

- Balance Autonomy and Control in Multi-Agent AI Environments (Amplework)

- Towards a Science of Scaling Agent Systems (Google Research)

- Levels of Autonomy for AI Agents (Knight Columbia)

- How Do Multi-Agent Systems Use Role Assignment (Milvus)

- AI Agent Memory for Stateful Systems (Redis)

- OpenAI Agents Python SDK (OpenAI)

- Agent Development Kit: Easy to Build Multi-Agent Applications (Google Developers)

- Top AI Agent Frameworks (IBM)

- Comparing AI Agent Frameworks: CrewAI, LangGraph, and BeeAI (IBM Developer)

- AI Agent Orchestration Frameworks (n8n)

- Build Production-Ready Multi-Agent AI on Azure AI Foundry (ITnext)

- Building a Multi-Agent System with Azure AI Agent Service (Microsoft Tech Community)

- 8 Strategies to Cut AI Agent Costs (DataGrid)

- Multi-Agent Coordination Strategies (Galileo AI)

- Debug Multi-Agent AI Systems (Galileo AI)

- 5 Essential Techniques for Debugging Multi-Agent Systems (Maxim AI)